Source: Commonwealth Fund study

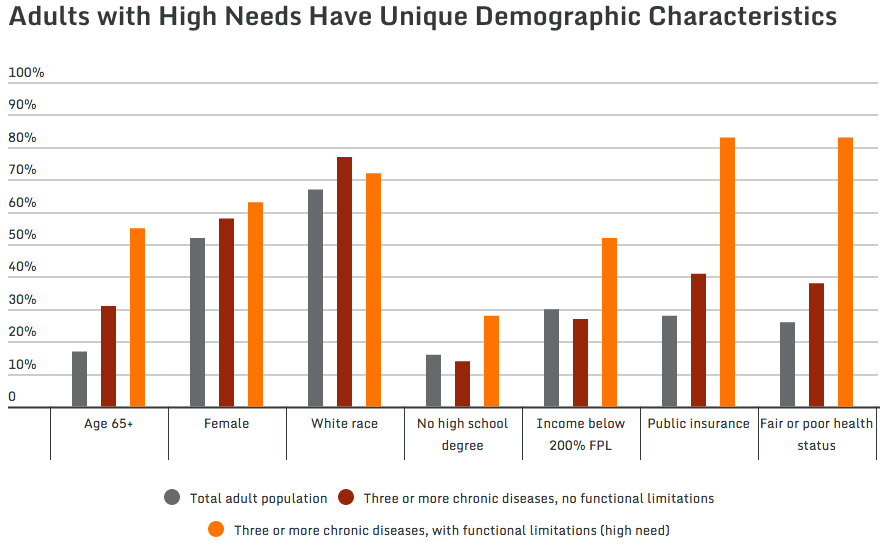

The highest-need adults are more likely to be white, female, poorer and less educated — and had drastically higher health costs and out-of-pocket expenses than adults overall, according to a new study from the Commonwealth Fund.

The authors set out to identify who the highest-need (and most expensive) patients were, and then identify ways to improve those patients’ outcomes while reducing spending.

Who are these patients? Check out the chart at the top of this post, or read the findings from the study:

High-need adults are disproportionately:

Older. More than half were age 65 and older; of these, most were 75 and older. In contrast, only about a third of adults with multiple chronic diseases, and less than a fifth of the adult population as a whole, were age 65 and older.

Female. Nearly two-thirds of adults with high needs were women, compared to just over half of the total population. This may reflect the fact that the majority of high-need adults are older and that women tend to live longer than men.

White. Nearly three-quarters of adults with high needs were white non-Hispanic—a higher share than in the adult population as a whole. Hispanic and Asian adults were underrepresented in both the high need and the multiple chronic diseases–only groups.5

Less educated. More than one of four high-need adults did not finish high school, compared with one of seven of those with multiple chronic diseases and about one of six in the total adult population.

Low income. More than half of adults with high needs had low incomes (i.e., below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, or less than $21,780 for an individual in 2011).6 This is nearly double the share in both the multiple chronic conditions–only group and the total adult population.

Fair or poor self-reported health. The combination of a functional limitation and multiple chronic conditions appears to lead to worse self-reported health than multiple chronic conditions alone. While more than four of five adults with high needs (83%) reported fair or poor health, fewer than two of five adults (38%) in the multiple chronic diseases–only group did so (Appendix Table 6).

These adults were also more likely to be persistently high-cost. The authors write:

We also looked at how “high-cost” individuals were distributed within the high-need and comparison groups. We defined individuals as having high health care costs if their total annual medical expenditures landed them among the top 10 percent or 5 percent of costliest patients in either one or both years they were observed in MEPS.

We found that high-need adults were more likely to remain high spenders over two years than adults with multiple chronic conditions only or adults overall (Exhibit 6, Appendix Table 1a). In the high-need group, for example, nearly one of six adults was in the top 5 percent of spending for two years in a row, as compared to only one of 50 adults in the group with multiple chronic diseases only. Since care management is typically more cost-effective when targeted to those who persistently incur higher costs, focusing on the high-need group may offer a better yield in identifying patients for intervention. However, given that the multiple chronic diseases–only group includes millions more people, even the very small percentages of this group that are persistently high cost may also represent an important opportunity for improvement.

So what does this all mean? From the study:

As health system reform shifts payment away from fee-for-service to value-based care models, the incentives to focus on and improve care for high-cost patients will grow. The share of adults who have multiple chronic diseases as well as a limitation that hinders their ability to carry out necessary daily activities such as bathing, eating, using the telephone, or taking medication is much smaller than the share with multiple chronic diseases alone. But, the former group have substantially higher average annual health care expenditures and out-of-pocket costs and are more likely to continue to incur high health care spending than their counterparts who are not functionally limited. In addition to higher costs, high-need adults also have lower incomes, making it more difficult for them to afford care. Thus, it is important to consider the unique needs of the subpopulation with functional limitations in combination with multiple chronic diseases when identifying patients for care models or care management programs.

Even among high-need patients, we found there is considerable variation in use and spending. This suggests the high-need population should be segmented into subgroups with common needs and health challenges. Payers and providers will need to take into account the persistence of high spending and patients’ amenability to change to better target and tailor interventions to meet particular needs and improve outcomes while achieving a return on their investment.